70 Montpelier Road

- Ninka Willcock

- Dec 27, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: 2 days ago

Home for Invalid Children

Elizabeth Ann Freeman (1812 – 1891)

The remit of Stevenage-born Robert Lee’s “select boarding school for young gentlemen” at 26 Regency Square was to prepare pupils for the public schools. In 1845, when the freeholder sought to sell the property, the school moved to the healthy heights of 70 Montpelier Road. The 1851 Census records just eight resident pupils, which was possibly unviable. At any rate, Lee's school disappears.

In 1855, Elizabeth Ann Freeman, founded here a Home for Invalid Children to provide sea air, nutritious food and medical care to youngsters, from impoverished urban families, who had "delicate constitutions" or were recuperating from illness. Initially, four children were admitted free of charge at Miss Freeman’s own expense.

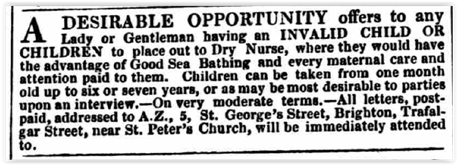

Recognition of the restorative properties of sea air and bathing provided commercial opportunities for lodging facilities specifically targeting the children of affluent parents. This advertisement, for example, was placed in the Brighton Gazette on July 23rd 1846:

Concerned about the want of medical care in such commercial “packages”, local doctors George Lowdell and John Newnham Winter were set on providing an alternative model:

Despite Lowdell and Winter's numerous attempts to promote the initiative, both locally and nationwide, the trail appears to go cold. Did the idea materialise in any form? Whether or not the Home for Invalid Children which opened five years later at 70 Montpelier Road, similarly embracing medical care, was an outcome of - or at least was directly influenced by - Lowdell and Winter’s endeavours awaits evidence.

With a focus on children whose parents could not afford the fees of commercial facilities, Miss Freeman's establishment is undoubtedly Brighton's first relatively ‘inclusive’ children’s convalescent home. And, for such a small-scale venture, it enjoyed an exceptionally long lifespan.

From the start, the Home appears to have been scrupulously managed. Dr Benjamin Ward Richardson’s Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Borough of Brighton (1882) notes that not one outbreak of infectious illness had occurred there since its foundation over a quarter of a century earlier. This was no mean feat given that many of the patients would have been immunocompromised.

About 18 children could be accommodated at any one time. Four were admitted free of charge but most parents paid for their child’s (or children’s) board. This payment, however, merely defrayed the actual cost. With all other expenses for operating the Home relying on voluntary donations and subscriptions, it is impressive that periods of “pecuniary embarrassment” were overcome, often by means of urgent appeals. By the end of 1890, just two months before her death, Miss Freeman reported that 2,945 children "had found rest and restorative treatment" at her Home.

Although Miss Kate Warren had taken over stewardship of the Home by January 1889, Miss Freeman remained as its honorary secretary. Increased competition in the provision of children’s convalescent homes, both locally and nationally, made it even harder to make ends meet, a situation compounded by Miss Freeman’s death in April 1891. Although her £2,000 legacy would have helped in due course, children were no longer admitted free of charge.

The establishment became known for a time as the Freeman Home in honour of its founder.

Was there teaching at the Home?

The Brighton Gazette on December 17th 1868 notes – somewhat enigmatically - that, although education was not “part of the offer”, teaching did take place “as far as circumstances would permit”. With most of the children only admitted for a maximum of two months, religious instruction was a higher priority than the 3Rs. Indeed, we are told that, “many little ones have first heard in the Home of the tender love of our Lord. . .”

Religious input, whether ad hoc or formal was close at hand. A number of Anglican clergymen lived nearby, some of whom were officially involved with the Home as well as well as with local National schools for children of the less affluent. Just over 30 years later, in 1889, the Nursing Record notes that Revd Pearson, the new incumbent of St Margaret’s, had followed his predecessor Revd Roxby as Chaplain to the Home where “inmates. . . are given regular instruction by him”.

Despite Miss Freeman’s spurious designation as “Head Mistress” in the 1871 Census, I have yet to find evidence of overtly secular teaching at the Home until 1881, the first Census year in which a resident teacher - Phoebe Wick - is recorded.

The Census conducted on the night of 5th April 1891 - less than two months after Miss Freeman’s death and with the Home now in the hands of Kate Warren - lists 29-year-old Ellen Lang as resident teacher. However, Lang’s tenure may have brief and quite possibly ended turbulently. On 11th August 1892, she was admitted, not from 70 Montpelier Road but from Brighton Workhouse, to the Sussex County Lunatic Asylum at Haywards Heath. Manifestations of her "mania" diagnosis included delusions, being noisy and “rambling conversation”, none of which would have been conducive to effective teaching.

Discharged from the Asylum in November 1892, Lang was taken into the home of her sister and brother-in-law at 19 Islingword Place. However, her physical health was described as “delicate” and she died five months later from phthisis (tuberculosis). Both the death certificate and the Asylum papers record her as a schoolmistress.

In the 1891 Census, several of the patients at 70 Montpelier Road are designated as "scholars", which at this time meant “attending a school, or receiving regular instruction at home”. What kind of instruction, though, and were the children receiving it before, after and/or during their stay at 70 Montpelier Road?

In the same vein, the 1901 Census records either “school boy” or “school girl” but there is no reference to a resident teacher (although he or she could, in theory, have been elsewhere that night).

Into the 20th century with Kate Warren (1855 - 1941)

Henry Charles Malden had retired in 1888 after 33 years as Headmaster of Windlesham House boys’ prep school when it was based nearby at Norfolk Terrace. Although no longer living locally, he is named as the Home’s secretary and treasurer in the 1897 and 1901 street directories.

In 1903, the Home moved to 59 York Rd, Hove, where Miss Warren remained in post into the early 1920s. Miss Hall then took over, succeeded by Mrs Clara Digby-White.

Even deeper into Hove

By 1948, with Mrs Digby-White still in post, the Home had relocated to 92 Cromwell Road. In 1965, the building, by this time owned by the Invalid Children's Aid Association, was acquired throughs a Compulsory Purchase Order by East Sussex County Council for conversion into "a senior hostel for mentally sub-normal adults".